Frontier Fields had a big presence at this year’s January meeting of the American Astronomical Society. On Jan. 7, there was a news release announcing the results of the first set of observations of galaxy cluster Abell 2744, along with a gorgeous image of the cluster. We met with Dr. Jennifer Lotz, the principal investigator for Frontier Fields to get an update and discuss these latest results.

Meet the Frontier Fields: Abell 2744

This is the first in a series of posts introducing and providing essential facts about each of the Frontier Fields.

Abell 2744, also known as Pandora’s Cluster, is a giant pile-up of four smaller galaxy clusters. Abell 2744, and its neighboring parallel field, are among the first targets of the Frontier Fields program.

The Abell catalogue of galaxy clusters was first compiled by astronomer George O. Abell in 1958, with over 2,700 galaxy clusters observable from the Northern Hemisphere. The Abell catalogue was updated in 1989 with galaxy clusters from the Southern Hemisphere.

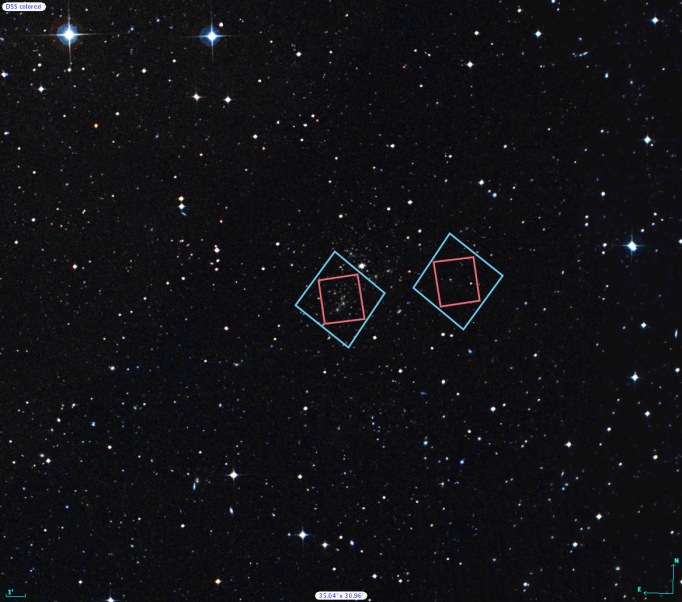

The locations of Hubble’s observations of the Abell 2744 galaxy cluster (left) and the adjacent parallel field (right) are plotted over a Digitized Sky Survey (DSS) image. The blue boxes outline the regions of Hubble’s visible-light observations, and the red boxes indicate areas of Hubble’s infrared-light observations. A scale bar in the lower left corner of the image indicates the size of the image on the sky. The scale bar corresponds to approximately 1/30th the apparent width of the full moon as seen from Earth. Astronomers refer to this unit of measurement as one arcminute, denoted as 1′.

Credit: Digitized Sky Survey (STScI/NASA) and Z. Levay (STScI).

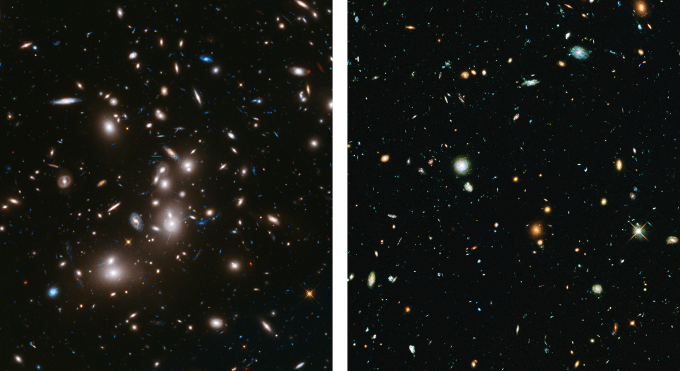

Shown here, with approximately half of the expected data included, are the early Frontier Fields images of Abell 2744 and the associated parallel field. Left: Frontier Fields image of the galaxy cluster Abell 2744 is displayed with colors chosen to highlight the newly obtained infrared data. The infrared-light data are shown in red. Visible-light data are included from archived observations and displayed in blue and green. Right: The new Frontier Fields image of the adjacent parallel field is displayed. In this image, all of the colors represent visible-light data.

Credit: NASA, ESA, and J. Lotz, M. Mountain, A. Koekemoer, and the HFF Team (STScI)

Estimated Dates of Observations: October-November 2013 and May-June 2014

The planned dates for Hubble observations of the Frontier Fields include observations approximately six months apart. This is the time it takes for the cameras on Hubble to swap positions so that both visible-light data and infrared-light data can be captured from the galaxy cluster field and the adjacent parallel field, as described in this post.

Galaxy Cluster Cosmological Redshift: 0.308

Redshift measures the lengthening of a light wave from an object that is moving away from an observer. For example, when a galaxy is traveling away from Earth, its observed wavelength shifts toward the red end of the electromagnetic spectrum. The galaxy cluster’s cosmological redshift refers to a lengthening of a light wave caused by the expansion of the universe. Light waves emitted by a galaxy cluster stretch as they travel through the expanding universe. The greater the redshift, the farther the light has traveled to reach us.

Galaxy Cluster Distance: approximately 3.5 billion light-years

Galaxy Cluster Field Coordinates (R.A., Dec.): 00:14:21.2, -30:23:50.1

Parallel Field Coordinates (R.A., Dec.): 00:13:53.6, -30:22:54.3

Constellation: Sculptor

Related Hubble News:

- Hubble and Spitzer Space Telescopes Find One of the Youngest Galaxies in the Universe

- Frontier Fields: Hubble Goes Deep (science content reading for students & educators)

- Hubble’s First Frontier Field Finds Thousands of Unseen, Faraway Galaxies

- NASA’s Great Observatories Begin Deepest Ever Probe of the Universe

- Pandora’s Cluster – Clash of the Titans

Looking for Hubble data used by scientists?

Frontier Fields in Two Minutes

The Frontier Fields project is an ambitious, multi-year cosmology research project using Hubble and many other telescopes. Describing the astronomy motivation, science concepts, planning, coordination, and execution is a long and daunting task. The Principal Investigator, Jennifer Lotz, recently gave a public-level presentation that was an hour long, with much of her discussion necessarily condensed.

Now, folks don’t always have that kind of time to spend learning about a new project. What about the short version: the so-called elevator pitch?

To address that need, we created a two-minute video overview of the Frontier Fields. We trimmed the astronomical story to its essentials, gathered and developed scientific visuals, and attempted to express it it all in just nine sentences.

The video below was part of our press release at the American Astronomical Society winter meeting in January 2014. It won’t make you a cosmology expert, but it will provide the essential character of one of the most important projects amongst Hubble’s current programs. I directed (and narrated) this video, and would welcome any comments or questions.

As for all those scientific details that we glossed over or skipped, well, that’s one of the main motivations of this blog. Stay tuned.

Frontier Fields: Exploring the Depths of the Universe

This video presents an overview of the Frontier Fields project. While Hubble has a celebrated history of deep field observations, astronomers can use massive galaxy clusters as gravitational lenses to see a little farther into space and a little further back in time. This ambitious, community-developed project is a collaboration among NASA’s Great Observatories to probe the earliest stages of galaxy development. Initial data from this multiyear effort was presented at the American Astronomical Society Meeting in January 2014.

Credit: NASA, ESA, and F. Summers, B. Lawton, M. Lussier, G. Bacon, and D. Coe (STScI)

Music: “The Moments of Our Mornings” (K. Engel)/CC BY-NC 3.0

Searching for Cosmic Dawn

Today’s guest post is by Hubble Space Telescope astrophysicist Dr. Jennifer Lotz.

How deep can we go? What is the faintest — and possibly most distant — galaxy we can see now with the Hubble Space Telescope? This is the challenge taken up by the Frontier Fields, a new campaign to see deeper into the universe than ever before.

It is thrilling to push past the limits of our knowledge of the universe. But the Frontier Fields are motivated by more than record-breaking. With a great deal of effort, Hubble is starting to capture light from galaxies that shows them as they appeared in the first few hundred million years of the universe. Sometime between the Big Bang — more than 13 billion years ago — and today, the Universe evolved from a hot, smooth sea of protons, electrons, and dark matter to a collection of billions of individual galaxies separated from each other by vast regions of mostly empty space. Within our own Milky Way galaxy are billions of stars forming out of clouds of gas, with planets surrounding almost every star. How did these “billions upon billions” come to be?

Because the speed of light is finite, astronomy is the only science in which it is possible to look back in time and directly observe the formation of galaxies and stars. The farther away an object is, the longer it takes for its light to reach us. Therefore, we see very distant objects as they were in the past — sometimes billions of years in the past. We call this “look-back time.”

Very distant galaxies with look-back times of 13 billion years or more appear very, very faint. Just how faint? The faintest objects that the Hubble Space Telescope has seen are galaxies whose light we have collected by looking a one small piece of sky for hundreds of hours — the Hubble Ultra Deep Field. Those objects are some 4 billion times fainter than the faintest star the human eye can see.

But it turns out that this may not be faint enough to see the era of cosmic dawn, when the lights from the first stars and galaxies turned on. Even with the Hubble Ultra Deep Field, we have just a handful of galaxies detected at these early times. Even though they appear very faint to us, these early galaxies we have seen are likely to be the biggest and brightest objects around at that time. In order to understand how and when galaxies like our own Milky Way first formed, we need to peer even deeper into the early universe.

Illustration of the depth by which Hubble imaged galaxies in prior Deep Field initiatives, in units of the Age of the Universe. The goal of the Frontier Fields is to peer back further than the Hubble Ultra Deep Field and get a wealth of images of galaxies as they existed in the first several hundred million years after the Big Bang. Note that the unit of time is not linear in this illustration. Illustration Credit: NASA and A. Feild (STScI).

The James Webb Space Telescope, with its much larger light-collecting area and infrared sensitivity, is designed to study these early galaxies in great detail. But JWST is still years away, and our knowledge about the first galaxies is extremely limited. By using a trick from Einstein’s theory of general relativity, Hubble is attempting to get a sneak peek at these very faint and distant galaxies.

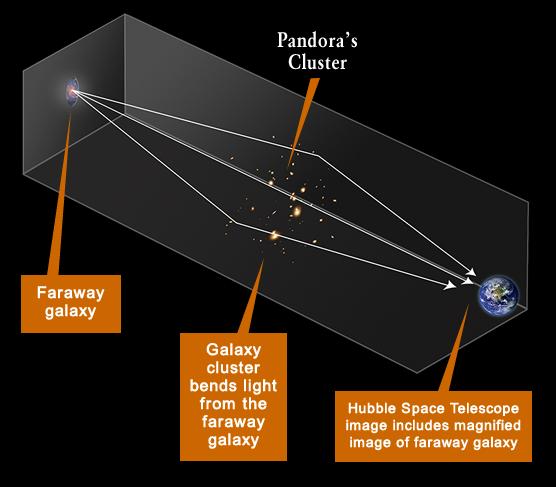

Illustration of how galaxy clusters can bend and redirect the light from distant background galaxies. Not only is the galaxy’s light bent back in our direction so that Hubble can view it, but it is also magnified. This technique provides a means by which we can detect faint distant galaxies that would otherwise be out of reach of Hubble’s capabilities. Illustration Credit: A. Feild (STScI)

The most massive objects in the Universe — very massive clusters of galaxies — bend space in such a way that light rays passing by a cluster will also be bent, much in the way light passing through a telescope is bent. This is called “gravitational lensing,” and these clusters act as nature’s telescope, magnifying and stretching the light from those galaxies located behind the clusters.

The Frontier Fields is observing six of these massive clusters of galaxies. Due to the boost from the cluster lensing, the images obtained by the Frontier Fields will probe galaxies ten to twenty times fainter than the objects seen in the Hubble Ultra Deep Field. In combination with six additional “parallel” fields, areas near the Frontier Fields regions that lack massive galaxy clusters but can be observed simultaneously to obtain additional “deep field” images, these images are expected to give us a better understanding of how and when galaxies like our Milky Way formed.

The very first data from the first cluster — Abell 2744 — has been taken:

The immense gravity in this foreground galaxy cluster, Abell 2744, warps space to brighten and magnify images of far-more-distant background galaxies as they looked over 12 billion years ago, not long after the Big Bang. This is the first of the Frontier Fields to be imaged. Credit: NASA, ESA, and J. Lotz, M. Mountain, A. Koekemoer, and the HFF Team (STScI)

As have the first observations of a parallel field:

In this “parallel field” to Abell 2744, Hubble resolves roughly 10,000 galaxies seen in visible light, most of which are randomly scattered galaxies. The blue galaxies are distant star-forming galaxies seen from up to 8 billion years ago; the handful of larger, red galaxies are in the outskirts of the Abell 2744 cluster. Credit: NASA, ESA, and J. Lotz, M. Mountain, A. Koekemoer, and the HFF Team (STScI)

While astronomers work to understand these first images, Hubble is moving on to the next cluster — MACS0416-2403. Expect many more beautiful and deep images over the next few years, and a new understanding of cosmic dawn.

Cosmic Archeology

Today’s guest post is by Dr. Mario Livio, Hubble astrophysicist and author of the blog “A Curious Mind.” A version of this post appeared previously on Dr. Livio’s blog.

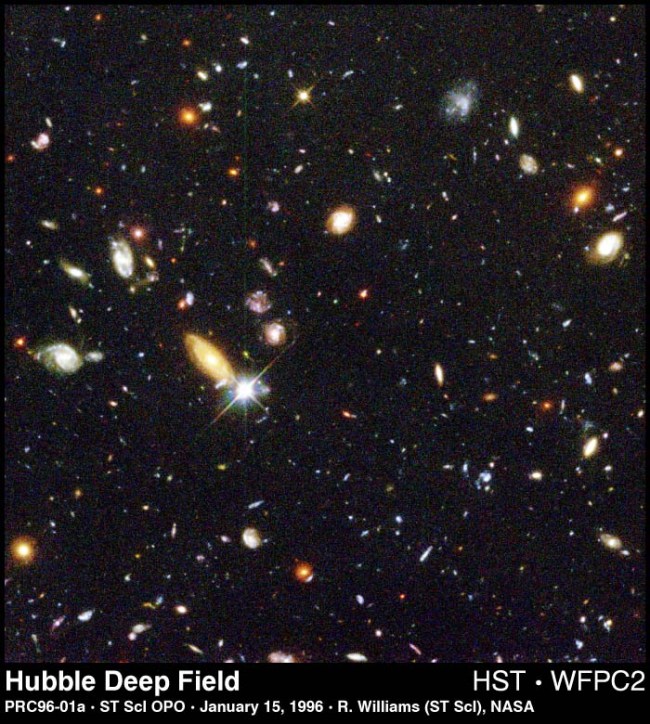

During the Christmas season of 1995, the Hubble Space Telescope was pointed for 10 consecutive days at an area in the sky not larger than the one you would see through a drinking straw. The region of sky, in the Ursa Major constellation, was selected so as to be as “boring” as possible — empty of stars in both our own Milky Way galaxy and in relatively nearby galaxies. The idea was for Hubble to take as deep an image of the distant universe as possible. The resulting image was astounding. With very few exceptions, every point of light in this image is an entire galaxy, with something like 100 billion stars like the Sun.

The original Hubble Deep Field image.

Detailed analysis revealed that the very remote galaxies were physically smaller in size than today’s galaxies, and that their morphologies were more disturbed. Unlike the grand-design spirals or smooth elliptical shapes that we see in relatively close galaxies, the distant objects look like train wrecks. Both of these observations fit nicely into the idea that galaxies evolve largely by “mergers and acquisitions.” Small building blocks merge together to form larger ones, or cold flows of dark matter along dense filaments fuel the growth. What we see in the distant past are those interacting—and hence smaller and less regular in shape—building blocks.

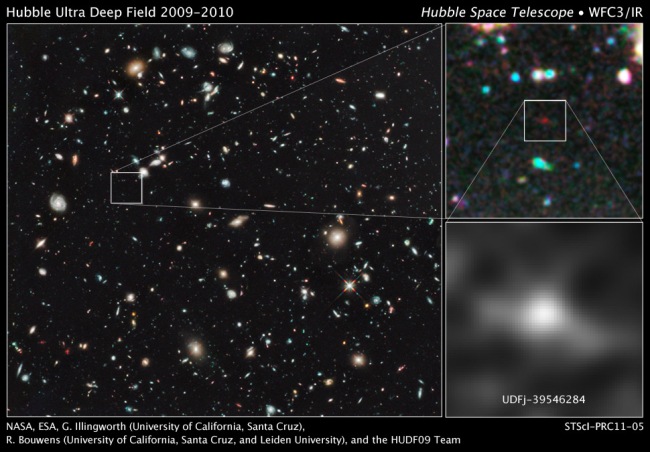

Since then, Hubble observed even deeper, producing the “Hubble Ultra Deep Field” in 2004, and then in 2009 an image that included infrared observations taken with the new Wide Field Camera 3. This observation allowed astronomers to glimpse the universe at its infancy, when it was less than 500 million years old (the universe today is 13.8 billion years old). The Deep Field observations have also enabled researchers to reconstruct the history of global cosmic star formation. We now know that about 8 billion years ago the universe reached its peak in terms of the new star-birth rate, and that rate has been declining ever since — our universe is past its prime.

This tiny object in the Hubble Ultra Deep Field is a compact galaxy of blue stars that existed 480 million years after the Big Bang. Its light traveled 13.2 billion years to reach Hubble.

The Chandra X-ray Observatory has created its own Deep Field observations, discovering hundreds of low-luminosity active galactic nuclei, where disks feed mass onto central black holes, and emit copious x-ray radiation.

Infrared observations with the Spitzer Space Telescope completed the picture of the deepest images of the cosmos to date. Together, Hubble, Chandra, and Spitzer have created a detailed tapestry of a dynamic, evolving universe in which some two hundred billion galaxies are within the reach of our present telescopes.

Currently, Hubble is engaged in observing six new deep fields, each one centering on a galaxy cluster whose gravity can deflect, multiply, and magnify the light from more distant objects (the effect is known as “gravitational lensing”). In parallel, Hubble will also observe six deep “blank” fields. The goal is to use those so-called “Frontier Fields” to reveal populations of fainter galaxies, and to characterize the morphologies of distant star-forming galaxies.

The first of these super-deep views of the universe has already revealed almost 3000 of previously unseen, distant galaxies.

To see the very first galaxies that formed in our universe, we will have to await the James Webb Space Telescope, on schedule for launch in 2018. From a cosmic perspective, new discoveries are just around the corner!

Cluster and Parallel Fields: Two for the Price of One

Hubble is doing double-duty as it peers into the distant universe to observe the Frontier Fields. While one of the telescope’s cameras looks at a massive cluster of galaxies, another camera will simultaneously view an adjacent patch of sky. This second region is called a “parallel field”—a seemingly sparse portion of sky that will provide a deep look into the early universe.

This image illustrates the “footprints” of the Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3) infrared detector, in red, and the visible-light Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS), in blue. An instrument’s footprint is the area on the sky it can observe in one pointing. These adjacent observations are taken in tandem. In six months, the cameras will swap places, with each observing the other’s previous location.

Many people are familiar with Hubble’s deep field images, where the telescope stared at what appeared to be relatively empty areas of the sky for long periods of time. Instead of a vast sea of blackness, what astronomers saw in these long exposures were thousands upon thousands of galaxies of all shapes and sizes.

But these deep fields covered just a small fraction of the area of the full moon on the sky. Do they really reflect what our universe looks like, or are these unusual regions? The truth is, astronomers just don’t know. That’s why they are adding to their knowledge by studying the six “parallel” deep fields in various locations across the sky. Whether or not they find similar galaxy-rich regions, they will learn something interesting about our universe.

Hubble simultaneously uses the Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS) for visible-light imaging, and Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3) for its infrared vision. So the infrared camera could observe the cluster while the visible-light camera focuses on the parallel field.

This diagram shows the light paths that originate with the galaxy cluster field and the neighboring parallel field. The light from the galaxy cluster field (red) is imaged with the Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3) infrared detector, while the light from the parallel field (blue) is imaged with the visible-light Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS). Hubble’s entire field of view is shown on the left side of the diagram. It includes the “footprints” of ACS (red) and WFC3 (blue), as well as those of the fine guidance sensors (FGSs), which are the three, white wedges on the outside, and everything in between them.

Six months later, the Earth will be at the opposite side of the sky in its yearly orbit around the Sun. The telescope, which is powered by solar arrays, has also pivoted 180 degrees to achieve the optimal orientation to illuminate the arrays. This opposite rotation means the cameras will effectively “swap places,” with each camera now observing the other’s previous location. Now the visible-light camera views the cluster while the infrared camera images the parallel field.

This diagram shows a detailed view of galaxy cluster Abell 2744, one of two massive galaxy clusters being imaged in the first year of Frontier Fields.

For each of the six cluster and six parallel fields, astronomers will have both infrared and visible-light observations. This will allow them to create more detailed, overlapping and complete images.

Over three years, 840 orbits will be devoted to these 12 fields. That’s about 2 million seconds of Hubble time. These data are taken in 15-20 minute exposures, and they come down to the ground as digital files. These images are then stitched together to create mosaics. The resulting views will give us new insight into the early universe.

This illustration shows the “footprints” of all the instruments in Hubble’s field of view. These include the fine guidance sensors (FGSs), the Near Infrared Camera and Multi-Object Spectrometer (NICMOS), the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS), the Cosmic Origins Spectrograph (COS), the Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3), and the Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS), which includes the Solar Blind Channel (SBC). WFC3 and ACS are the two instruments involved in the Frontier Fields program.

Frontier Fields Hangout Highlights

For those who would rather not sit through the whole hangout (and I really can’ t imagine why you wouldn’t since it was very interesting), I’ve taken the time to index some of the more interesting topics discussed during the hour. Click on the topic below to go to that part of the hangout.

- What is Frontier Fields?

- Why is the survey called Frontier Fields?

- What is gravitational lensing?

- How/Why does dark matter contribute to cluster lensing?

- How do we know dark matter is in these clusters? How do we ‘see’ it?

- Awesome gravitational lensing demonstration by Dan Coe

- How were the galaxy clusters chosen?

- Will the James Webb Space Telescope be able to see these clusters?

- Why are distant galaxies not visible at optical wavelengths? Why are they in the infrared?

- How are the Frontier Field observations taken?

- How long will Hubble stare at these fields?

- How will the lensed and distorted galaxies be de-lensed?

Please stay tuned for more Hubble Hangouts on the Frontier Fields as the project progresses. We are planning more hangouts that discuss the role of dark matter in the Frontier Fields clusters, how to get the data yourself from the Hubble archive, and much more!

Supernova Discovered in One of the Frontier Fields

The data had hardly started coming through the pipeline when astronomers made the first Frontier Field discovery: a supernova in the galaxy cluster MACSJ0717, one of the first of the Frontier Fields to be imaged.

The Frontier Fields designation for this object is SN HFF13Zar, and its nickame is “SN Zara.”

Supernovae discovery is an offshoot of Frontier Fields science because Hubble will be revisiting many of these fields several times over the next three years, allowing astronomers to compare recent images with older ones, and look for things that are different.

The supernova is located 1.73 arcmin from the center of the MACSJ0171 cluster and is a whopping 23.53 (+- 0.05) magnitude.

I say whopping, but big numbers on the magnitude scale mean an object is very, very dim. This is definitely a faint supernova, but not out of the ordinary in terms of what Hubble can see. Hubble can see things as faint as 31st magnitude, which is slightly fainter than objects that can be viewed by the best ground-based telescopes.

Without getting too crazy into the magnitude scale topic, suffice it to say for our purposes that

One magnitude thus corresponds to a brightness difference of exactly the fifth root of 100, or very close to 2.512 — a value known as the Pogson ratio. Source: Sky and Telescope

Aren’t you glad you asked?

So the supernova is faint, but Hubble can see it without problems, as you can tell from the right panel, in which a purple circle marks the supernova. The left panel in this image is a compilation of observations taken in 2006 and prior with Hubble’s Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS).

SN HFF12Zar was discovered using the F814W filter, known as the i band in the ACS.

The supernova’s home is still unknown — it could have occurred in one of three potential galaxies within 5 arcsec of the stellar explosion. These galaxies are labelled in the above image as A (orange), B (red) and C (light blue).

The other circles, D (green) and E (yellow) are other galaxies probably not associated with the supernova.

The redshift of the galaxy cluster is z=0.5458 (~10 billion LY away) and according to Dr. Steven Rodney (JHU), Dr. Jennifer Lotz (STScI), and Dr. Louis-Gregory Strolger (STScI), if the supernova is associated with host galaxy candidates A or B, it is a foreground object. If it’s associated with host galaxy candidate C, then it could plausibly be a SN from a galaxy in the outskirts of the cluster.

We’ll be revisiting this cluster again with Hubble in December 2013, as part of the Grism Lens Amplified Survey from Space (GLASS) proposal, but this supernova will probably be faded by the time Hubble looks this way again. However Steve Rodney and Lou Strolger have a program to search the Frontier Fields data for new supernovae as it comes in; if they find something that is potentially very interesting — very distant and/or lensed by the cluster, they will trigger extra Hubble observations of the supernovae to determine the type of supernova and exact distance.

First Hubble Hangout Featuring Frontier Fields

Please join us for our first Hubble Hangout that features the Frontier Fields Survey.

Please join us for our first Hubble Hangout that features the Frontier Fields Survey.

A collaboration of astronomers are poised to make observations with the Hubble Space Telescope that will provide us with the deepest views we’ve ever had of the cosmos and give us a glimpse of what the James Webb Space Telescope will routinely provide us.

Known as the Frontier Fields survey, this revolutionary deep field program will combine the power of the Hubble Space Telescope with the natural gravitational telescopes of high-magnification clusters of galaxies. Using both the Wide Field Camera 3 and Advanced Camera for Surveys in parallel, HST will produce the deepest observations of clusters and their lensed galaxies ever obtained, and the second-deepest observations of blank fields (located near the clusters).

These images will reveal distant galaxy populations ~10-100 times fainter than any previously observed, improve our statistical understanding of galaxies during the epoch of reionization, and provide unprecedented measurements of the dark matter within massive clusters.

The Frontier Field Survey will be pushing the limits of our beloved space telescope, making it more powerful than ever before, and providing us with some of the most important images ever taken.

Our goal is to have more of these as the project progresses, so please follow our g+ page to learn about future hangouts as they are scheduled.