The Frontier Fields Project has been an ambitious campaign to see deep into our universe. Gravitational lensing, as used by the Frontier Fields Project, enables Hubble to see fainter and more-distant galaxies than would otherwise be possible. These images push to the very limits of how deeply Hubble can see out into space.

Hubble, Spitzer, Chandra, and other observatories are doing cutting-edge science through the Frontier Fields Project, but there’s a challenge. Even though leveraging gravitational lensing has allowed astronomers to see objects that otherwise could not be detected with today’s telescopes, the technique still isn’t enough to see the most distant galaxies. As the universe expands, light gets stretched into longer and longer wavelengths, beyond the visible and near-infrared wavelengths Hubble can detect. To see the most distant galaxies, one needs a space telescope with Hubble’s keen resolution, but at infrared wavelengths.

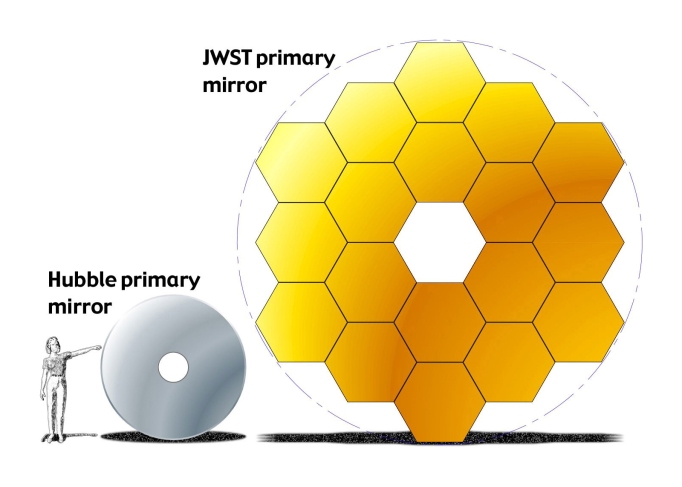

That infrared telescope is the James Webb Space Telescope, slated to launch in October 2018. It has a mirror 6.5 meters (21 feet) across, can observe wavelengths up to 10 times longer than Hubble can observe, and is the mission that will detect and study the first appearances of galaxies in the universe.

Figure 1: Webb will have a 6.5-meter-diameter primary mirror, which would give it a significant larger collecting area than the mirrors available on the current generation of space telescopes. Hubble’s mirror is a much smaller 2.4 meters in diameter, and its corresponding collecting area is 4.5 square meters, giving Webb around seven times more collecting area! Webb’s field of view is more than 15 times larger than the NICMOS near-infrared camera on Hubble. It also will have significantly better spatial resolution than is available with the infrared Spitzer Space Telescope. Credit: NASA. http://webbtelescope.org/gallery

Observations of the early universe are still incomplete. To build the full cosmological history of our universe, we need to see how the first stars and galaxies formed, and how those galaxies evolved into the grand structures we see today.

Looking back in time to the first light in the universe:

Astronomers use light to explore the universe, but there are pieces of our universe’s early history where there wasn’t much light. The era of the universe called the “Dark Ages” is as mysterious as its name implies. Shortly after the Big Bang, our universe was filled with glowing plasma, or ionized gas. As the universe cooled and expanded, electrons and protons began to bind together to form neutral hydrogen atoms (one proton and one electron each). The last of the light from the Big Bang escaped (becoming what we now detect as the Cosmic Microwave Background). The universe would have been a dark place, with no sources of light to reveal this cooling, neutral hydrogen gas.

Some of that gas would have begun coalescing into dense clumps, pulled together by gravity. As these clumps grew larger, they would become stars and eventually galaxies. Slowly, starlight would begin to shine in the universe. Eventually, as the early stars grew in numbers and brightness, they would have emitted enough ultraviolet light to “reionize” the universe by stripping electrons off neutral hydrogen atoms, leaving behind individual protons. This process created a hot plasma of free electrons and protons. At this point, the light from star and galaxy formation could travel freely across space and illuminate the universe. It is important to note here, astronomers are currently unsure whether the energy responsible for reionization came from stars in the early-forming galaxies; rather, it might have come from hot gas surrounding massive black holes or some even more exotic source such as decaying dark matter.

The universe’s first stars, believed to be 30 to 300 times as massive as our Sun and millions of times as bright, would have burned for only a few million years before dying in tremendous explosions, or “supernovae.” These explosions spewed the recently manufactured chemical elements of stars outward into the universe before the expiring stars collapsed into black holes.

Astronomers know the universe became reionized because when they look back at quasars — incredibly bright objects thought to be powered by supermassive black holes — in the distant universe, they don’t see the dimming of their light that would occur if the light passed through a fog of neutral hydrogen gas. While they find clouds of neutral hydrogen gas, they see almost no signs of neutral hydrogen gas in the matter located in the space between galaxies. This means that at some point the matter was reionized. Exactly when this occurred is one of the questions Webb will help answer, by looking for glimpses of very distant objects still dimmed by neutral hydrogen gas.

Much remains to be uncovered about the time of reionization. The universe right after the Big Bang would have consisted of hydrogen, helium, and a small amount of lithium. But the stars we see today also contain heavier elements — elements that are created inside stars. So how did those first stars form from such limited ingredients? Webb may not be able to see the very first stars of the Dark Ages, but it’ll witness the generation of stars immediately following, and analyze the kinds of materials they contain.

Webb’s ability to see the infrared light from the most distant objects in the universe will allow it to truly identify the sources that gave rise to reionization. For the first time, we will be able to see the stars and quasars that unleashed enough energy to illuminate the universe again.

Figure 2: JWST will be able to see back to when the first bright objects (stars and galaxies) were forming in the early universe. Credit: STScI. http://jwst.nasa.gov/firstlight.html

Early Galaxies:

Webb will also show us how early galaxies formed from those first clumps of stars. Scientists suspect the black holes born from the explosions of the earliest stars (supernovae) devoured gas and stars around them, becoming the extremely bright objects called “mini-quasars.” The mini-quasars, in turn, may have grown and merged to become the huge black holes found in the centers of present-day galaxies. Webb will try to find and understand these supernovae and mini-quasars to put theories of early galaxy formation to the test. Do all early galaxies have these mini-quasars or only some? These regions give off infrared light as the gas around them cools, allowing Webb to glean information about how mini-quasars in the early universe work — how hot they are, for instance, and how dense.

Webb will show us whether the first galaxies formed along lines and webs of dark matter, as expected, and when. Right now we know the first galaxies formed anywhere from 378,000 years to 1 billion years after the Big Bang. Many models have been created to explain which era gave rise to galaxies, but Webb will pinpoint the precise time period.

Hubble is known for its deep-field images, which capture slices of the universe throughout time. But these images stop at the point beyond which Hubble’s vision cannot reach. Webb will fill in the gaps in these images, extending them back to the Dark Ages. Working together, Hubble and Webb will help us visualize much more of the universe than we ever have before, creating for us an unprecedented picture that stretches from the current day to the beginning of the recognizable universe.

Figure 3: This illustration shows the cold side of the Webb telescope, where the mirrors and instruments are positioned. Credit: Northrop Grumman. http://webbtelescope.org/gallery

Resources:

https://frontierfields.org/2016/07/21/the-final-frontier-of-the-universe/