[Note: this article is cross-posted on the Hubble’s Universe Unfiltered blog.]

Fifty years ago, in 1966, the Star Trek television series debuted. Given the incredible longevity of the franchise, it seems remarkable that the original television series only lasted three seasons.

Each episode famously began with the words “Space: the final frontier.” To me, those thoughts evoke an idea of staring into the night sky and yearning to know what is out there. They succinctly capture an innate desire for exploration, adventure, and understanding. Such passions are the same ones that drive astronomers to decipher the universe through science.

While Captain Kirk and company could make a physical voyage into interstellar space, our technology has (so far) only taken humans to the Moon and sent our probes across the solar system. For the rest of the cosmos, we must embark on an intellectual journey. Telescopes like Hubble are the vehicles that bring the universe to us.

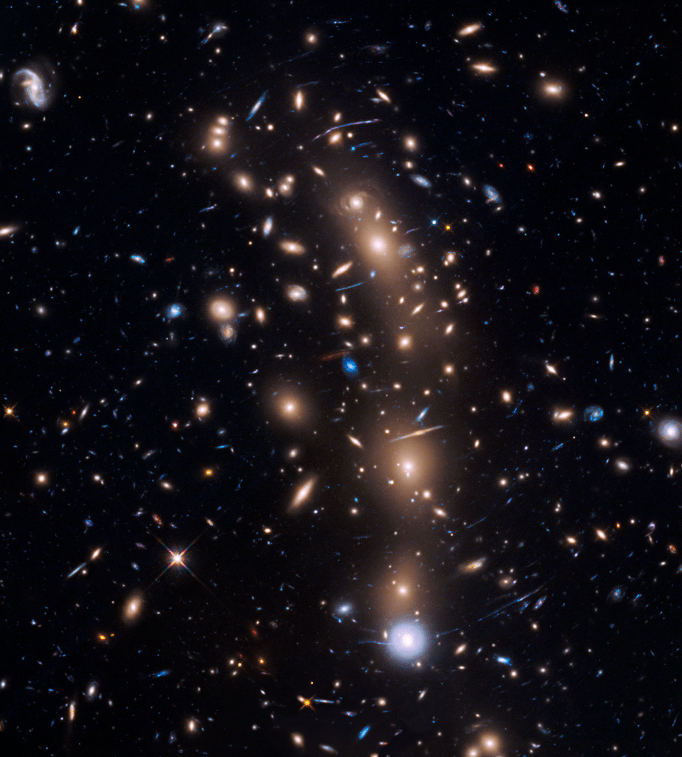

To explore remote destinations, the Enterprise relied upon a faster-than-light warp drive. Astronomy, in turn, can take advantage of gravitational warps in space-time to boost the light of distant galaxies. Large clusters of galaxies are so massive that, under the dictates of general relativity, they warp the space around them. Light that travels through that warped space is redirected, distorted, and amplified by this “gravitational lensing.”

Gravitational lensing enables Hubble to see fainter and more-distant galaxies than would otherwise be possible. It is the essential “warp factor” that motivates the Frontier Fields project, one of the largest Hubble observation programs ever. The “frontier” in the name of the project reflects that these images will push to the very limits of how deeply Hubble can see out into space.

But is this the “final frontier” of astronomy? Not yet.

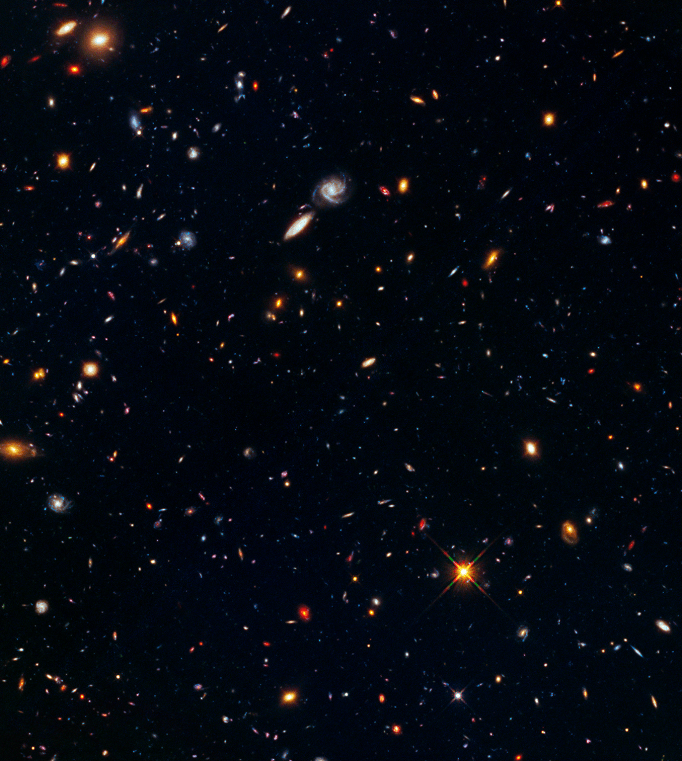

Abell S1063 Parallel Field – This deep galaxy image is of a random field located near the galaxy cluster Abell S1063. As part of the Frontier Fields Project, while one of Hubble’s instruments was observing the cluster, another instrument observed this field in parallel. These deep fields provide invaluable images and statistics about galaxies stretching toward the edge of the observable universe.

The expanding universe stretches the light that travels across it. Light from very distant galaxies travels across the expanding universe for so long that it becomes stretched beyond the visible and near-infrared wavelengths Hubble can detect. To see the most distant galaxies, one needs a space telescope with Hubble’s keen resolution, but at infrared wavelengths.

In what may have been an homage to the Star Trek television series with Captain Picard, the project for such a telescope was originally called the “Next Generation Space Telescope.” Today we know it as the James Webb Space Telescope, and it is slated to launch in October 2018. Webb has a mirror 6.5 meters (21 feet) across, can observe wavelengths up to ten times longer than Hubble can observe, and is the mission that will detect and study the first appearances of galaxies in the universe.

In the Star Trek adventures, Federation starships explore our galaxy, and much of that only within our local quadrant. Astronomical observatories do the same for scientific studies of planets, stars, and nebulae in our Milky Way; and go beyond to galaxies across millions and billions of light-years of space. Telescopes like Hubble and Webb carry that investigation yet further, past giant clusters of galaxies, and out to the deepest reaches of the cosmos. With deference to Gene Roddenberry, one might say “Space telescopes: the final frontier of the universe.”